Valentine Maninger left Germany in 1854, at age 18. We know details about his passage from Germany to Le Havre, and his Atlantic crossing aboard the Mercury. We have the passenger list showing his arrival at Castle Garden in New York City.

He was in America. Where would he go? What would he do?

What would you have done?

Scouring the ship’s passenger list, we don’t find any of the familiar surnames from Dittwar. Val traveled alone.

We know Val ended up in Woodford County in central Illinois. Examining census and citations for Woodford and surrounding counties, we can’t find any of the Dittwar surnames.

So why did Valentine Maninger end up in a small village in Illinois? The answer is serendipitous. It’s because of the Amish.

A chance meeting

Val Maninger was Catholic, as was everyone else in Dittwar. Val had probably never heard the word Amish. But during his month-long voyage on the Mercury, he met Amish families on their way to Illinois.

Though Val didn’t have a known destination, the Amish travelers did. Their families and neighbors had preceded them, and had sent back letters and instructions and promises. The new travelers knew exactly where they were going, and had somewhere to stay when they arrived.

To Val, that must have sounded like a good plan.

Here’s a compelling page from the book “Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County.” It’s a passenger list excerpt from the Mercury’s May 1854 voyage listing Amish families bound for Illinois. This is the same sailing that Valentine was on.

The Mercury arrived at New York May 20, 1854, carrying 569 passengers. Among them were Waglers, Röschlis, Wagners traveling to Tazewell, Woodford, and McLean Counties in Central Illinois.

Passenger list excerpt – Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County

The book “Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County” includes passenger lists for other sailings, each with lists of Amish immigrants bound for the same counties in Illinois.

Amish in Illinois

These Amish families were destined for a three-county area in central Illinois, where there were already established Amish communities. The families on the Mercury passenger list can be found in censuses in Tazewell and Woodford Counties. Val Maninger became their neighbor.

The following are surnames of Amish families in Tazewell, Woodford, and McLean Counties in 1860. These are the same names as Valentine’s neighbors, including his future wife and many in-laws. The book “Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County” includes genealogy research on 103 Amish families that populated these counties.

Think back to the subtitle of Bob Henderson’s book – “The Maninger Family: with additional sections on the related families of Barth, Smith, Schrock, Weyeneth.” The Smith and Schrock families were Amish, and were already residents of these counties.

Conclusion

Valentine Maninger boarded the Mercury at Le Havre in April 1854, not knowing his destination in America.

By the time he disembarked in New York in May, Val had decided to travel with the Amish families to Illinois.

Three waves of Amish immigration

Amish and Mennonite followers fled Bern and Zurich and the Swiss Confederacy to escape persecution, and perhaps death. Many traveled down the Rhine River to Alsace and Lorraine, under control of France. They leased land from French landowners, who were only too happy to have such pious and industrious tenants.

The first wave of Amish and Mennonite immigrants arrived in William Penn’s colony in the late 1600s and early 1700s. They famously settled in Lancaster County and west across the Susquehanna River in York County, Pennsylvania. Later their descendants traveled west to Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois.

The second wave of Amish arrived in the 1830s. In eastern Lorraine and Lower Alsace there had been poor harvests, and now there were increased threats of military conscription. Many of the immigrants settled in Ohio first, later moving to Illinois for unsold and inexpensive government land.

The third wave happened in the mid-1800s. There were popular uprisings in Germany and France and Austria. Most of the revolutions failed, and the autocrats took revenge on the lower and middle classes. This was the largest wave of Amish immigration. As we know, this third wave also brought along an 18-year-old German Catholic boy.

By 1850 Illinois had 851,470 residents, an increase of 189,320 in five years. Foreign-born residents made up almost 22 percent of the population of Tazewell County, and German speakers made up the largest number of immigrants.

The fastest growing and largest Amish community was in McLean County, next to Tazewell County. By the mid-1850s the settlement consisted of five church districts, and Central Illinois held a total of eight – twice as many as Pennsylvania.

Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County

Nibbles Extra Credit – What’s Amish? What’s Mennonite?

Let’s take a brief look at these questions. What’s Amish? What’s Mennonite?

If you asked Grandpa and Grandma Troyer and King and Kaufman and Ropp and Schad and Stalter, “Are you Mennonite?” they would have said, “No, mir sin Amish.” Well, that settles it. They were Amish.

Of course, that was only a division that came into this church long ago. We hardly know what it was, but we have one good rule to go by to know if they are Amish. If you had asked an Amishman of 1840, “What are your son’s names?” and he had said, “John, Joe, Jake, Pete, and Chris,” that settled it. He was Amish.

Walter Ropp’s recollections

OK, that was a fun look, but let’s learn a bit more. Here’s a bare-bones history.

The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, aka the Protestant Reformation, was a theological movement that challenged the abuses and corruption of the Roman Catholic Church. Martin Luther published his “Ninety-five Theses” in 1517 in Germany. These argued, among other things, that selling indulgences for the forgiveness of sins was wrong.

In 1521, Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X, and the Holy Roman Emperor banned anyone from defending Luther’s ideas.

Anabaptists

Around 1518, Huldrych Zwingli, a priest in the Church of Zurich, became the Reformation’s leader in the Swiss Confederacy.

Zwingli proposed that life should be governed by the literal word of the Holy Scriptures. He felt forgiveness of sins was possible without buying an indulgence.

At first, Zwingli stated that baptism be done at an age where someone could give informed consent. Infants aren’t able to make an informed decision.

But by 1522, he backed away from his positions, and endorsed baptism of infants. His followers saw these actions as concessions to the City Council of Zurich, and split with him.

These breakaway factions maintained a belief in informed adult baptism. By 1525, they began to meet and baptize one another.

They became known as Anabaptists, which means second baptism.

Anabaptists were severely persecuted by the government and the church. The penalty was exile or death. Many left Bern and Zurich and relocated to Alsace and Lorraine.

On Jan. 4, 1528, the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Charles V issued a mandate to ruling princes, “…That each and every Anabaptist and rebaptized person, man or woman of accountable age, shall be brought from natural life to death with fire and sword and the like.”

Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County

Mennonites

Menno Simons was a Catholic priest from the Netherlands.

In 1531, Simons was horrified to witness the church behead someone who had been re-baptized as an adult. He searched the Bible in vain for guidance on infant baptism.

Menno’s brother Pieter was among a group of Anabaptists killed in a religious cloister in 1535. Menno withdrew from the priesthood.

Mennonites refused to bear arms for the government or to take an oath of loyalty.

Menno Simon’s followers are Mennonites.

Amish

Jacob Amman was a Mennonite who held even more conservative views.

Halbtäufer (halfway Anabaptist) were those who accepted Anabaptism, but were afraid of publicly renouncing the state Reformed Protestant Church. Amman believed that Halbtäufer, or tolerance, would dilute faith. He stressed a Ban, or excommunication, avoiding and shunning those who weren’t strict in their religious behavior.

Hans Reist, a Mennonite leader, argued that fallen believers should only be withheld from communion, and not regular meals. Jacob Amman argued that those who had been banned should be avoided even in common meals.

In 1693, Amman set up two meetings with Hans Reist, but Reist didn’t appear at either. Amman placed Reist under the Ban. In return, Reist excommunicated Amman. That was the Amish Division.

Amman’s followers are Amish.

OK, who came to Illinois?

There were both Amish and Mennonite immigrants to the central counties in Illinois, but the communities of interest to us are Amish.

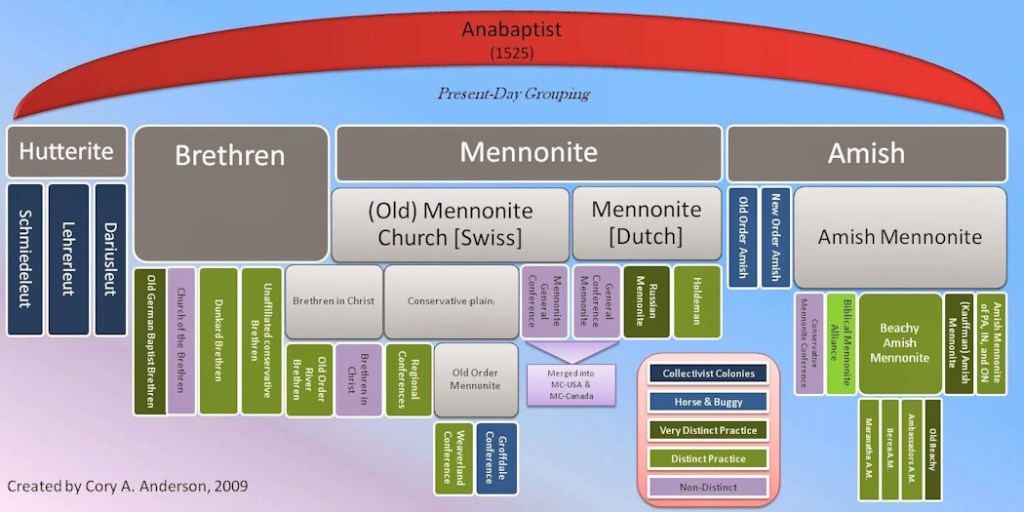

My explanations and diagrams are simplistic. There are many more branches in the Anabaptist pedigree. Here’s a more complete diagram.

Sources:

- Image – Immigrant at Castle Garden – https://www.amazon.com/Immigrants-Castle-Arrived-Photograph-Century/dp/B07C4XWS29

- Image – Passenger list excerpt – Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County – Part One of Five – Page 43 – Joseph Peter Staker – 2022 – https://tcghs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Amish-Mennonites-01.pdf

- Image – Emigrants below deck at night tracing the ships progress – Illustrated London News – January 20, 1849 – https://www.iln.org.uk/iln_years/year/1849.htm

- Image – Amish surnames – Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County – Appendix – Page 59 – Joseph Peter Staker – 2022 – https://tcghs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Amish-Mennonites-Appendix.pdf

- Image – Illinois population 1850s – Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County – Appendix – Page 42 – Joseph Peter Staker – 2022 – https://tcghs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Amish-Mennonites-Appendix.pdf

- Map – Illinois County Map – Johnson – 1860 – Maps of the Past – https://www.mapsofthepast.com/illinois-state-map-il-browning-1860.html

- Quote – Amish settlement patterns – A genealogical study of the Nicolaus and Veronica (Zimerman) Roth family, 1834-1954 – by Ruth C. Roth and Roy D. Roth – 1955 – https://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupid?key=ha005693071

- Quote – How to tell is someone is Amish – Walter Ropp recollections – Family History Library – FHL microfilm 182369

- Image – Decree against Anabaptists – Amish Mennonites in Tazewell County – Appendix – Page 9 – Joseph Peter Staker – 2022 – https://tcghs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Amish-Mennonites-01.pdf

- Image – Huldrych Zwingli – By Hans Asper – Winterthur Kunstmuseum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=553075

- Image – Martin Luther – by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Martin_Luther_by_Cranach-restoration.jpg

- Image – Menno Simons – Wikipedia – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Menno_Simons.jpg

- Image – Pencil sketch of Jakob Ammann with a background of the valley where he lived near Markirch – mikeatnip – 18 July 2012 – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jakob_Ammann.tif

- Map – Disturnell’s new map of the United States and Canada : showing all the canals, rail roads, telegraph lines and principal stage routes – Henry A Burr – 1850 – Library of Congress – https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3700.fi000031/?r=-0.199,-0.016,1.111,0.881,0

- Image – Anabaptist diagram – Cory A Anderson – Pennsylvania State University, Population Research Institute – https://pennstate.academia.edu/CoryAnderson

- Family Tree diagrams – Ancestry.com and Mark Jarvis

- Music – Awakening – Spectacular Sound Productions – Free Music Archive – https://freemusicarchive.org/music/Spectacular_Sound_Productions/single/awakening/

Thanks for providing historical background on the Mennonites vs. the Amish. I knew about the Anabaptists but was unaware that their religious beliefs led to the two, stricter denominations. Very interesting!

LikeLike

Just to let you know I’ve been

LikeLike

Hi Louise,

So great to hear from you. Hope you’re well and feisty. I’m honored that you’re still reading Nibbles.

Love Mark

LikeLike